One of the biggest issues in cargo quality preservation during shipping by sea is sweat-induced moisture damage. It can occur on any voyage and has resulted in massive cargo loss over history. It is important that every mariner is aware of the principle of sweat — what it is, why it happens, and how to prevent it.

Image Source: Britannia P & I Club

What is Ship Sweat?

Two main types of sweat that can damage cargo exist:

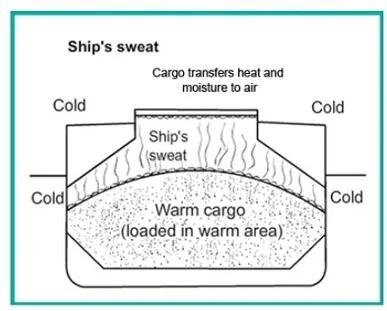

- Ship Sweat

This is when warm air, i.e., loaded with moisture in a ventilated hold, becomes cold and condenses on cold ship structures made up of steel decks, bulkheads, or frames.

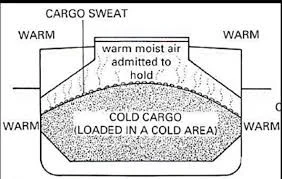

- Cargo Sweat

This is when warm, humid air, drips straight onto cold cargo surfaces and causes condensation on the surface of the cargo.

Both of these conditions can result in corrosion damage, stains, mould, or other deterioration.

What Causes Sweat?

Sweat occurs due to temperature, moisture, and condensation.

The most important factor here is dew point, or when air cannot hold moisture any more and begins to condense.

If the cargo temperature is less than the dew point of the air coming in to the vessel, moisture will condense on the cargo (cargo sweat).

If the structure temperature of the vessel is less than the dew point of the air in the hold, moisture will condense on the vessel structure (ship sweat).

Sources of Cargo Hold Moisture

Moisture may arise from:

Humid external air entering through ventilation.

Rain, snow, or sea water intrusion via hatches or vents.

Moist cargo, dunnage, or packaging materials.

Hygroscopic cargoes that release moisture.

Leaks in ship structure or piping systems.

Hot-to-Cold vs. Cold-to-Hot Rule

A basic rule mariners apply:

“Hot to Cold – Ventilate Hold. Cold to Hot – Ventilate Not.”

Hot to Cold: In moving from hot to cold climates, ventilation can prevent hot, moist air from condensing on cold surfaces.

Cold to Hot: When shipping from cold to warm climates, prevent ventilation to keep warm, moist air away from cold cargo surfaces.

Examples of Sweat Damage

Steel Products: When loaded cold in cold weather northern ports, if warm tropical humid air is allowed to ventilate cargo before it warms and passes through the dew point, it is likely to sweat.

Canned Goods: Prolonged ventilation while under warm, humid conditions causes increased rusting and damage to labels.

Mixed Cargoes: Moisture from the warm cargo may be released as vapor and may condense on cooler surfaces above.

Wet Timber: Moisture released from wet timber as vapor can condense under decks and drip on the adjacent cargo.

How to Avoid Sweat Damage

- Check Dew Point and Cargo Temperatures

Employ wet and dry bulb thermometers (psychrometers) to determine air temperature and humidity.

Compare outside air dew point with cargo temperature prior to ventilating.

- Ventilate Only When Safe

Maintain holds closed if external air dew point is above cargo temperature.

Ventilate if outside air dew point is below both cargo and steel temperatures.

- Prevent Unnecessary Ventilation

Propping open ships’ hatches at all times and continuously ventilating can do more harm than benefit.

- Observe Sudden Temperature Fluctuations

Sudden decreases in air or seawater temperature may lead to unforeseen condensation.

- Manage Sources of Moisture

Have hatches shut during rain or rough seas.

Shun the carriage of wet cargo unless unavoidable, and secure it away from delicate cargo.

Key Points for Seafarers

Dew point is the most critical consideration in avoiding sweat.

Ventilation must be a measured, deliberate process — not an automatic response.

Cargo damage due to sweat can largely be avoided by good monitoring and judgment.

Bridge and cargo teams’ awareness and training are essential for avoiding losses.

Final Word:

By honoring the principle of condensation and keeping dew point under close watch, ship crews can avoid a great deal of sweat damage. It’s not ventilating day and night — it’s ventilating at the proper time.